A BBC undercover investigation has revealed a deeply disturbing story in the European migrant crisis, one that plays out miles from the English Channel, in the heart of Essen, Germany. Here, under layers of clandestine activity, smugglers have turned what they call “packages” of inflatable dinghies and life vests into lifelines for desperate migrants hoping to cross to the UK.

Uncovering the Network Behind Channel Smugglers

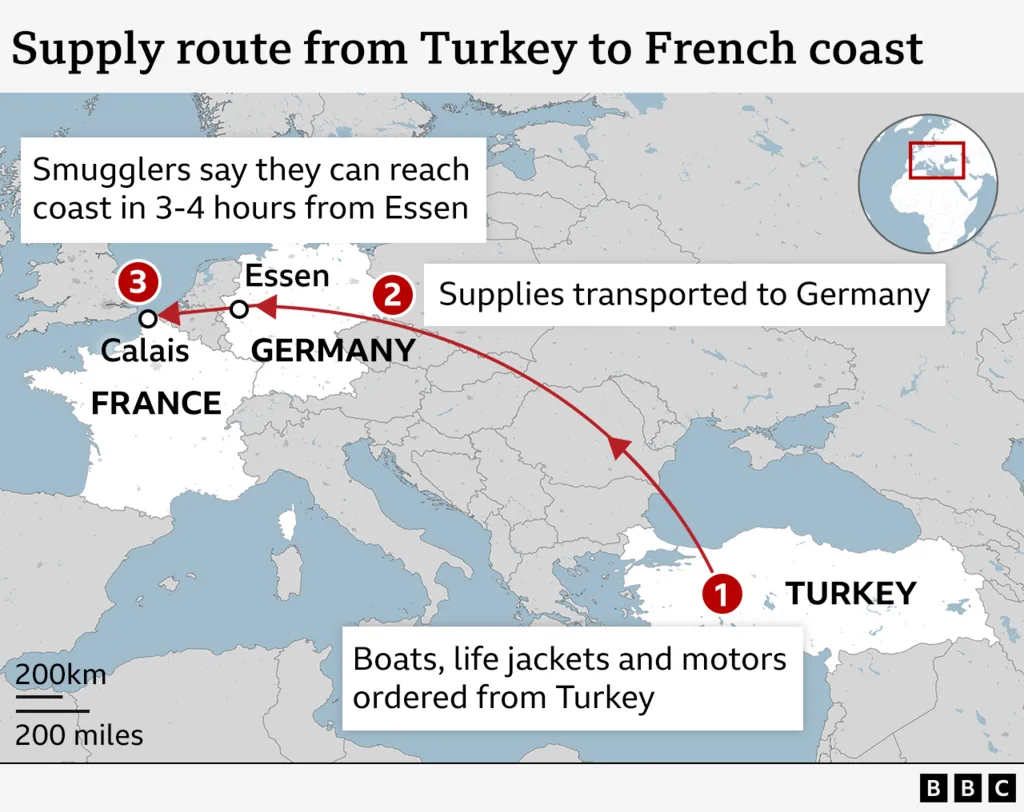

The investigation, spanning five months, showed how essential Germany has become in the logistical web of the smuggling business. Boats, motors, and life jackets make their way from China to Turkey and, eventually, to Essen. According to the National Crime Agency (NCA), smugglers stash these supplies in hidden warehouses across western Germany, a region removed enough from the Channel’s shores but close enough to move swiftly to northern France within hours.

A primary figure in this network, identified only as “Abu Sahar,” revealed to the BBC undercover reporter that for €15,000, smugglers can arrange an entire “package” that includes a boat, engine, and 60 life jackets, allegedly enough for a single trip across the Channel.

Smugglers Use German Loopholes

According to Germany’s Interior Ministry, assisting smuggling operations to a non-EU nation like the UK is technically not illegal on German soil. A UK Home Office source expressed “frustration” with Germany’s position, noting that the complex legal boundaries are exploited by criminal networks that use German territory for storage and logistical support while supplying smugglers along France’s Channel coast.

Sahar mentioned that this logistical advantage makes Essen a strategic point. “Calais is hard to reach,” he shared. German authorities, though aware of the activity, lack the jurisdiction to prosecute smuggling to non-EU destinations directly. Cooperation with French and Belgian authorities has led to recent arrests, yet smugglers continue to use Germany’s legal gray area to avoid conviction.

A System Funded in Cash and Secrecy

Sahar explained to “Hamza,” the undercover journalist posing as a Middle Eastern migrant, that payments are best made through Turkey’s hawala system. Cash never exchanges hands in Europe; instead, funds are delivered through a network of agents in Turkey. “This way,” says Khal, a higher-level operative in the network, “all the stuff” comes through without a trace, circumventing European financial systems.

Hamza, under tight surveillance, managed to see the operation firsthand, with smugglers sending him videos of dinghies stashed in storage, and outboard motors idling, awaiting their next shipment. According to Sahar, a new “crossing point” has emerged, likely to evade France’s vigilant police surveillance.

Elon Musk Backs Trump: What Does the World’s Richest Man Really Want?

The Brutal Reality of Channel Crossings

This year marks the deadliest on record for Channel crossings. As small, flimsy boats—some called “death traps”—make their way across the turbulent waters, migrants face incredible risks, often crammed into these unseaworthy vessels. Neil Dalton, Chair of the National Independent Lifeboat Association, underscored the inherent dangers, remarking that the boats provided by smugglers are dangerously fragile. “I wouldn’t go in a duck pond with these,” he said bluntly, highlighting the grim reality awaiting those who try to cross.

This network, fueled by “extraordinary” profits, endangers the lives of people seeking safety, only to meet uncertainty, or worse, tragedy at sea.

Europe’s Response: The Fight to End Smuggling Networks

As UK Home Secretary Yvette Cooper puts it, the smuggling trade has “been getting away with it for far too long.” Germany and the UK have begun setting up a new joint Border Security Command aimed at dismantling the smuggling routes through stronger cross-border cooperation. The BBC investigation shines a light on the smuggling networks’ reach and exposes the need for decisive action to dismantle operations before more lives are lost.