In the grand annals of medical history, there are some truly bizarre procedures. Bloodletting, leeches, even shock therapy—medicine wasn’t always pretty. But few procedures top the sheer jaw-dropping weirdness of trepanation—the act of drilling a hole into someone’s skull.

Yes, you read that right. For over 10,000 years, trepanation has been performed for reasons that range from the spiritual to the surgical.

In a world before X-rays or neurosurgeons, trepanation was the go-to for everything from treating epilepsy to curing “evil spirits.” And, despite its bloody reputation, people actually survived it—and sometimes even benefited from it.

What Is Trepanation?

At its core, trepanation is a surgical procedure where a hole is drilled into the human skull to expose the dura mater—the thick membrane surrounding the brain.

This technique is as ancient as it is widespread, with evidence of trepanned skulls found across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

But this wasn’t just some freak accident of history or a misguided medieval torture technique. Trepanation had real medical, spiritual, and cultural purposes.

From prehistoric skulls showing signs of healing to modern-day attempts to use it for mental clarity, trepanation has a long—and often disturbing—history.

Trepanation in the Ancient World

Let’s wind the clock back—way back, to about 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. This was a time when surgical precision didn’t involve laser beams or MRI machines. It involved stone tools and guts—literally.

Archaeological evidence shows that ancient civilizations, ranging from the Incas of South America to the Celts of Europe, were performing trepanation long before the first written language.

Tools made from flint, obsidian, or sharpened seashells were used to scrape or drill through the skull. Sounds like a nightmare, right? But it wasn’t seen as such by the patients—or the practitioners.

For many cultures, trepanation was an essential form of surgery, used to treat everything from head injuries to spiritual afflictions.

Why Drill a Hole in the Head?

In many ancient cultures, trepanation was believed to alleviate a wide range of medical issues.

- Head Trauma: In societies like the Inca Empire or early medieval Europe, head injuries from battles or falls were common. Trepanation allowed for pressure relief or the removal of shattered bone fragments.

- Epilepsy and Mental Illness: In some cases, the procedure was used to treat neurological disorders like epilepsy, which ancient cultures often saw as spiritual afflictions rather than medical conditions. If you were experiencing seizures, it was likely seen as a possession by evil spirits—something trepanation would ‘cure’ by allowing the spirits to escape.

- Spiritual and Ritualistic Practices: The spiritual significance of trepanation cannot be overstated. In regions like ancient Russia, trepanned skulls found near Rostov-on-Don suggest that the procedure had ritualistic importance. Trepanation marks found in these skulls were located in particularly dangerous areas of the head, such as the “obelion” (where a high ponytail would lie), suggesting that the surgery was less about survival and more about spiritual transformation or initiation.

Trepanning Methods: A Journey Through the Tools of the Trade

Different cultures developed their own techniques for performing trepanation, using the tools and knowledge available at the time.

Flint and obsidian were favored by ancient cultures like the Incas and the Neolithic Europeans for their sharpness and precision.

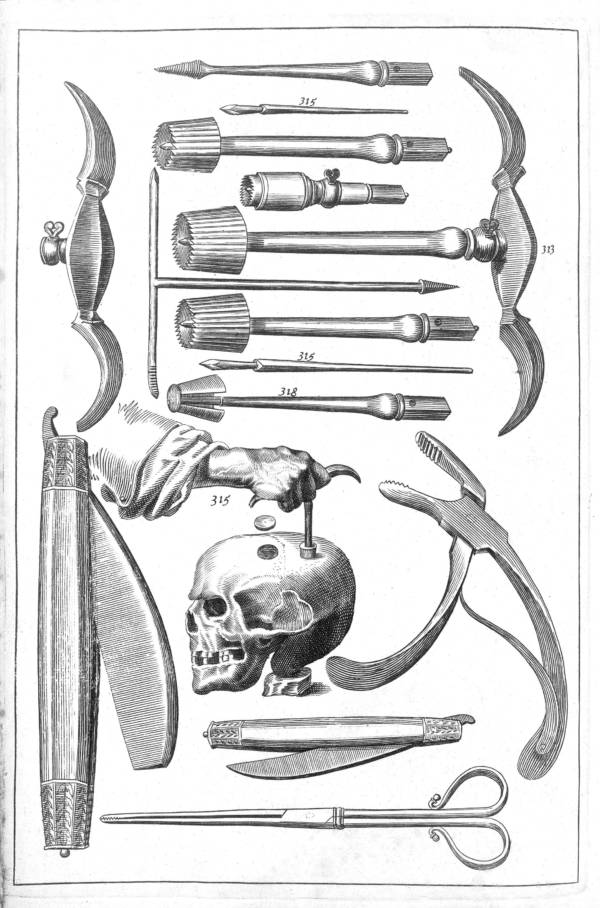

Later, metal tools became the norm, with the Greeks and Romans developing specialized instruments such as the terebra serrata, a rolling drill designed to pierce the skull without causing too much damage. Sounds fancy, but the patient still had no anesthesia, so let’s not sugarcoat the agony they went through.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the various trepanation methods that evolved over time:

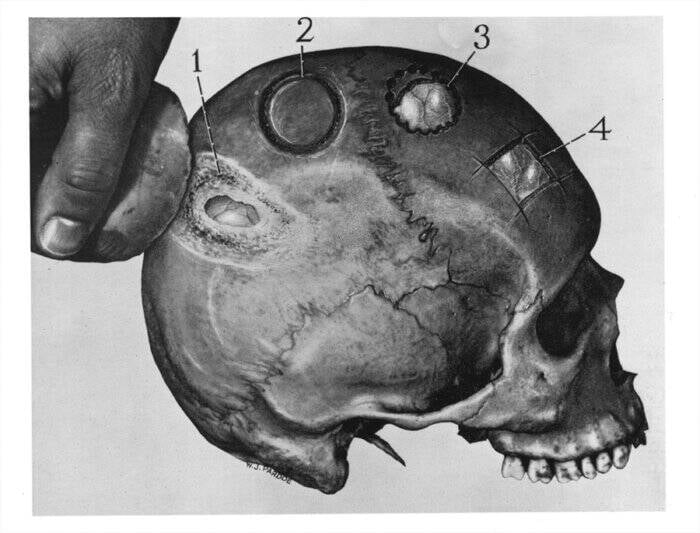

- Scraping: One of the oldest methods, where layers of bone were slowly scraped away with a sharp stone or tool. This was the most common method used in prehistoric times.

- Rectangular Intersecting Cuts: A method that involved creating intersecting cuts to remove rectangular sections of the skull.

- Grooving: Surgeons would create a circular groove in the skull and then lift the disc of bone off, revealing the dura mater.

- Circular Trephine or Crown Saw: This method involved drilling a circular hole into the skull using a saw-like instrument.

- Boring and Cutting: Tiny holes were drilled close together, and then the bone between them was carefully chiseled away.

Each method had its own risks, but none of them could prevent the dangers of infection or severe bleeding. It was all a gamble—and one with shockingly high stakes. Yet, despite the crude tools, survival rates were surprisingly high for a procedure that involved cutting into the skull. Depending on the culture and skill of the practitioner, survival rates in some regions like Peru hovered between 50% and 90%.

Trepanation Across the Globe: A Universal Procedure

The Greeks, Romans, and Incas weren’t the only ones who saw the potential in trepanation. Evidence of this ancient practice has been found in cultures worldwide, each with its own reasons for chipping away at people’s skulls.

Europe and Asia

Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, documented trepanation in the 5th century B.C.E., discussing it as a way to treat head wounds. In his Hippocratic Corpus, he offered detailed instructions for the procedure, like plunging the trephine into cold water to avoid heating the bone.

Hippocrates wasn’t the only one keeping an eye on skull surgery; the Romans also perfected their tools, developing devices like the terebra serrata, which would go on to inspire modern neurosurgical tools.

China also has a long, though less well-known, history of trepanation. In 2007, archaeologists uncovered skulls from the Neolithic through Iron Ages, showing that the practice had been more widespread than previously thought.

While China lacks detailed historical documentation of the procedure, there are hints in ancient literature, such as Ming Dynasty novels that reference skull surgery.

The Americas

In South America, the Incas were pioneers of trepanation. They had a remarkably high success rate, thanks to their advanced understanding of anatomy and healing.

Trepanned skulls discovered in Peru show signs of survival after the procedure, with some patients undergoing multiple surgeries during their lifetime. In these societies, trepanation was primarily used to treat head injuries sustained in combat or falls, but it also had spiritual connotations.

Africa and the South Pacific

In East Africa, trepanation was well-known, with evidence suggesting that tribal communities were still practicing it as recently as the early 1990s. Meanwhile, in the South Pacific, sharpened seashells were often used as tools for trepanation, offering a unique glimpse into how various cultures adapted the procedure to their local environments.

Modern Trepanation: From Medicine to Metaphysics

While ancient trepanation was mostly a medical necessity or spiritual ritual, modern trepanation has taken on a whole new dimension. In today’s world, the procedure is still performed in medical settings under a different name: the craniotomy.

This surgery is often used to remove brain tumors, relieve pressure after a traumatic brain injury, or take brain tissue samples for diagnostic purposes.

But here’s the kicker—some people still voluntarily undergo trepanation today, but for reasons far beyond medical necessity.

The 1960s and the Birth of Modern Self-Trepanation

The idea of using trepanation to enhance mental clarity or achieve a state of permanent “high” emerged in the 1960s, thanks to people like Bart Huges, a Dutch librarian who famously performed trepanation on himself using a dental drill.

Huges believed that drilling a hole in his head would improve brain function and expand consciousness. Spoiler alert: it didn’t.

Huges’ bizarre ideas caught the attention of others, including British author Joey Mellen, who went on to perform three trepanations on himself.

He detailed his experience in his book Bore Hole, claiming that the procedure enhanced his mental powers.

Mellen’s partner, Amanda Feilding, also tried her hand (literally) at trepanation, performing the procedure on herself with an electric drill. According to her, the experience was like “the tide coming in,” and she felt more mentally “light” afterward.

The Risks of Modern-Day Trepanation

Needless to say, modern medical professionals are not exactly on board with self-trepanation. Even with today’s advanced surgical techniques, craniotomies carry significant risks, including seizures, strokes, and infections. Attempting to perform a procedure like this at home? That’s a whole new level of dangerous. And no, despite what some may claim, there’s no scientific evidence that trepanation improves brain function or offers any mental or spiritual benefits.

A Hole in the Head That Stood the Test of Time

Trepanation is one of those practices that leaves you equal parts horrified and fascinated. It’s a testament to the lengths humanity has gone to in the name of healing—whether it’s curing epilepsy, treating battle wounds, or chasing spiritual enlightenment. From ancient flint scrapers to modern electric drills, the idea of drilling a hole in the head has persisted for millennia.