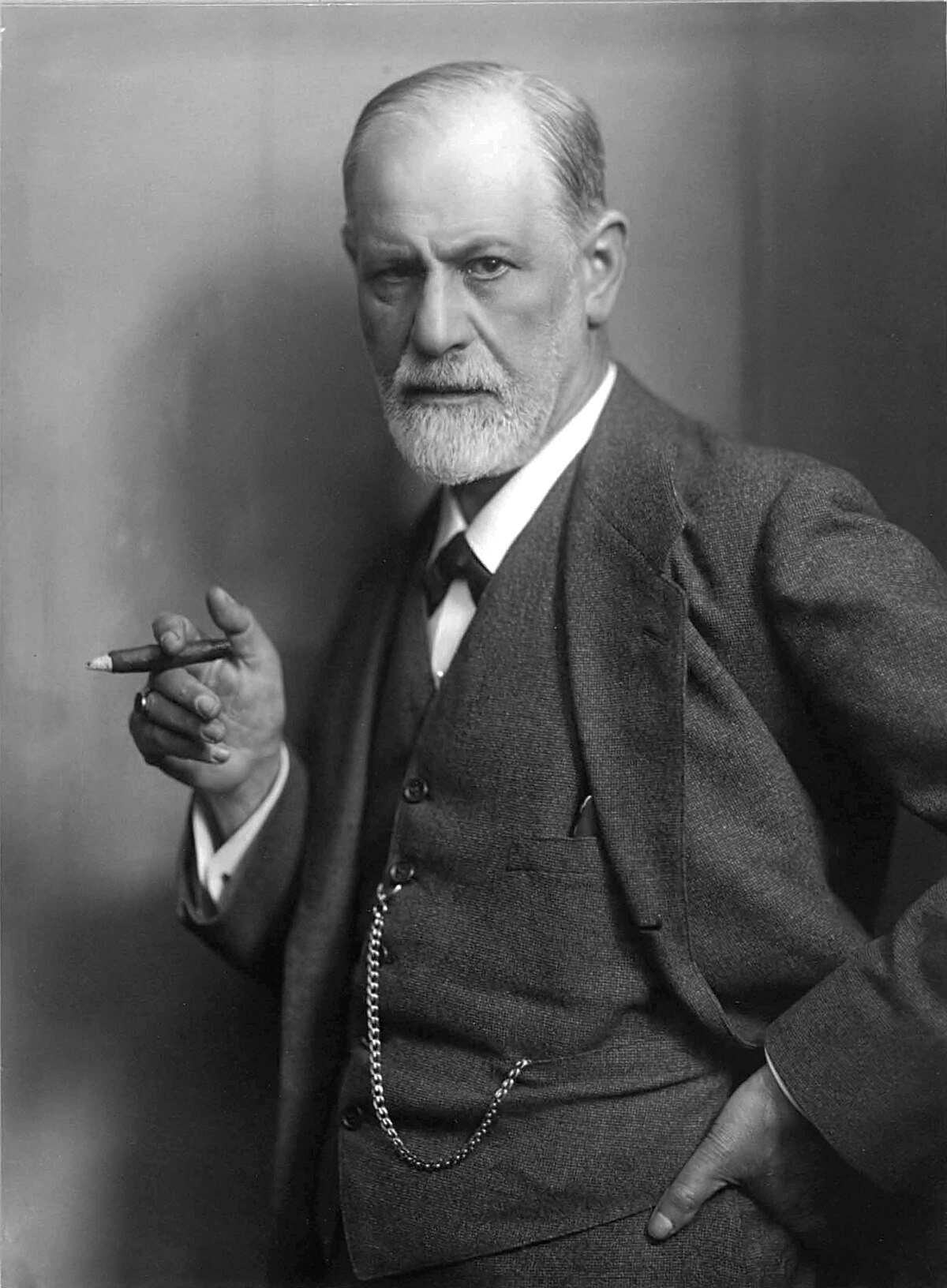

When the Nazis began their campaign of terror against intellectual freedom, they didn’t just stop at silencing voices—they went after the very words themselves. On May 10, 1933, across dozens of cities in Germany, the Nazis orchestrated public book burnings. These weren’t spontaneous acts of mob violence but carefully staged events, with university students and Nazi officials cheering as piles of books went up in flames. Sigmund Freud, a man whose works had revolutionized the understanding of the human psyche, found himself on the wrong side of this brutal purge.

Freud’s response to learning that his books were among those being burned is the stuff of legend. “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages, they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books.” It’s a biting observation, laden with sarcasm and a touch of gallows humor. Freud, ever the keen observer of human nature, saw the irony in how far society had come—or rather, how little it had. Back in the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church had a nasty habit of burning heretics at the stake, anyone whose ideas strayed too far from accepted doctrine. Freud understood that, in a way, the Nazis were carrying on this tradition. They were just a bit more “civilized” about it.

To Freud, this was a perverse kind of progress. The Middle Ages were an era of superstition and religious dogma, where questioning the church could lead to a death sentence. Fast forward to the 20th century, and while society had supposedly advanced, the same underlying fear of new ideas remained. The Nazis, with their racist and authoritarian ideology, couldn’t tolerate anything that threatened their control over the German people’s minds. Freud’s work, with its focus on the unconscious, sexuality, and the complexities of human behavior, was a direct challenge to the simple, brute-force worldview the Nazis were trying to impose.

Freud’s books were part of a larger list of works deemed “un-German,” which included everything from political treatises to children’s literature. The Nazi regime was meticulous in its efforts to cleanse German culture of what it considered “degenerate” influences. This wasn’t just about targeting Jewish authors, although that was certainly a big part of it. The Nazis also went after books by socialists, pacifists, and anyone who promoted ideas that ran counter to their fascist ideology(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,The National WWII Museum).

Freud’s life in Vienna became increasingly precarious as the Nazi grip tightened. Though he had long been a prominent figure in the intellectual world, his Jewish heritage made him a target. After Germany annexed Austria in 1938, the situation became dire. The Gestapo raided his apartment, interrogated his daughter Anna, and made it clear that Freud’s days in Vienna were numbered. It was only through the intervention of friends and admirers, including the Princess Marie Bonaparte, that Freud was able to secure an exit visa and flee to London. Freud was 82 years old and battling cancer when he left his home for the last time. He took with him some of his most prized possessions, but the majority of his extensive library and collection of antiquities were left behind.

Freud’s escape to London didn’t mean he was free from the horrors that had engulfed Europe. Four of his sisters, who were too old or sick to leave Vienna, were eventually deported to Nazi concentration camps where they perished. Freud’s own health continued to decline, and he died just over a year later, in 1939, shortly after the outbreak of World War II(The HISTORY Channel).

The burning of Freud’s books was not just an act of censorship, but part of a broader strategy by the Nazis to reshape German culture into something that served their twisted agenda. Book burnings were highly symbolic acts, meant to demonstrate the power of the regime and to intimidate anyone who might think of opposing it. Heinrich Heine, a German poet whose works were also burned, once wrote, “Where they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn people.” This prophecy was tragically fulfilled as the Nazis moved from burning books to committing genocide.

For Freud, the destruction of his books was a sign of the fragility of civilization. He had spent his life trying to bring light to the darkest corners of the human mind, to understand the irrational forces that drive behavior. But the events of the 1930s and 1940s showed that even in the modern world, those dark forces were alive and well. Freud’s quip about progress was a recognition of this disturbing reality. Even though humanity had made incredible advances in science, technology, and culture, the same primitive fears and hatreds that fueled the Inquisition were still at work.

In the end, Freud’s legacy survived the flames. Despite the Nazis’ best efforts, his ideas continued to influence psychology, literature, and the arts long after the war ended. The Nazis could burn his books, but they couldn’t erase the impact he had on the world. Freud’s work remains a testament to the power of ideas to endure, even in the face of tyranny. And his sardonic remark about progress serves as a reminder that the battle against ignorance and oppression is ongoing, that the darkness Freud sought to illuminate is never fully vanquished(The National WWII Museum,The HISTORY Channel).